Part 1: A Conversation with Michael and Shizuka Blaskowsky, the Translator Team behind SATO THE RABBIT

In Yuki Ainoya’s Sato the Rabbit, the first picture book in a trilogy from Japan, even the most routine activities transform into magical adventures with the titular Sato. Michael and Shizuka Blaskowsky, the husband-and-wife team who translated Sato into English, speak with Enchanted Lion’s Emilie Robert Wong about the differences between American and Japanese storybooks, the immersive power of illustrations, and the endless possibilities of Sato’s dreamlike and fantastical world. This is part one of the interview, which took place on October 29, 2020 (read the second and final part here).

Want to learn more about the whimsical Sato the Rabbit series and the art of translating children’s literature? Join Michael and Shiz, in conversation with Enchanted Lion, in a live Crowdcast event happening Sunday, March 7, 4–5 pm ET (tickets available here)!

ERW: To begin, how and why did you become a translator?

MB: I studied Japanese in high school and a little bit in college and did a study abroad. After college, I ended up moving to Japan for what turned into seven years. While living there, I tried a little bit of fan-subbing for animes and things like that, just in my spare time, and I liked it pretty well. Shizuka and I met while I was teaching English in Japan, and after dating for two years, we got married there before deciding to move to the U.S. together. Shiz had always wanted to take a world trip, so we combined returning to the States with a nine-month backpacking trip through Asia and parts of Africa and Europe, before moving to Seattle.

I got a job with a company importing Japanese products, but after five years there, I was looking for something to challenge me more creatively. And we wanted to travel around the States and central and south America more, so we were looking for a job that we could do while traveling. I went to some freelancing websites and started doing some Japanese-English translation at nights, and really enjoyed that. I began translating in my free hours, and when the company I worked for was sold, we moved to translating full time.

The company I worked for allowed me to work remotely, so slightly before it was sold, we rented our house and began traveling around the U.S. while working full time—and translating at night. After the sale, we started translating full-time while traveling, and we’ve been doing that ever since. Right now, we’re traveling around in a camper van—well, not so much these days; this year, we’ve been very stationary! I love to translate and feel like I found a profession that really suits me.

In January 2021, we’ll be coming up on five years as freelance translators. It all started from very casual, tiny jobs. I started asking Shizuka questions about the things I was working on, and that evolved into us really working more closely together, where I would do the translation, and then Shiz would look it over, and we’d talk about places that maybe needed improvement, places she felt like the real feeling or nuance of the Japanese wasn’t quite included in the English sentence. I think we both enjoy having someone with whom to shoot ideas back and forth, to talk about what would make the best sentence that conveys what the Japanese is trying to convey.

SB: At first, it was just a second job, so it wasn’t really a lot of work and my part wasn’t that big, but now, we are doing it full-time. We are always working as a team, and since we’ve been doing translation for five years now, we have a good structure as we go about it.

ERW: How did you first find out about Sato, and what were your first impressions and reactions when you read the book?

SB: It’s an interesting story, because we were living in Seattle; we didn’t find it in Japan. We were looking for Japanese books for our kid at the Seattle Library, and we found the Japanese version of Sato. We both liked the pictures and stories, so we brought it home, and we started reading it to our son. At the time, he was maybe five months old, and of course we couldn’t get his opinion, but we really liked it. We really liked the story. It’s so different from other children’s books: it’s so surreal, and it’s not really for young kids. It’s probably not for two- or three-year-olds, maybe more like five or something. I really like the world created in the books.

When we went back to Japan, we immediately bought all three Sato books: we knew we were taking them home. We have so many friends who have kids that we wanted to introduce to Sato, but they don’t understand Japanese. We explained to them what Sato is all about, but it’s really hard to explain the books well. That was the first time we realized, “I wish we could find these books in English,” and then Michael made it happen!

ERW: You said that you felt like Sato was different from other picture books. Do you mean that it’s different from picture books in Japan, different from picture books that you would normally find here in the United States?

SB: Hmm, I’d say it’s different in both Japanese and English. It’s just so—I don’t know…

MB: Shiz said “surreal” earlier, and that’s the word that I always associate with it. I do think Japanese picture books tend to be a little less story-driven, I’d say. I feel like—and I don’t mean this in a bad way, but I feel like less happens in a Japanese book per se than an English storybook. I just feel like they tend to be a little bit more about…

SB: Day-to-day life?

MB: Yeah. Actually, we found Enchanted Lion Books through the Chirri and Chirra series, and I think that’s a pretty good example of something that would happen in a Japanese picture book: the girls were riding a bicycle in a forest, and they found a bear’s house, and they ate cake. And that would just be the whole story! It’s less conflict-driven, I would say, perhaps than English stories, so I do think Sato’s a little more similar to other Japanese books in that regard, but it is very different from a lot of Japanese picture books, too.

ERW: Right, that cultural difference is really interesting. Even for other Japanese stories for children, like a Miyazaki film versus a Disney film, what you’re saying is totally true. It’s a slower, more intentional pace, and there’s a lot of room for moments in nature and moments of reflection and pauses, whereas American movies and books are often very action- and plot-heavy, as if things need to be happening at all times to keep everybody’s attention. That’s actually one of the reasons why Enchanted Lion publishes so many books in translation from other countries, to open up those new perspectives for readers in the United States who wouldn’t have access to them otherwise.

Michael, when you were first reading Sato to your child, did anything catch your eye in particular as a translator, in terms of a tricky passage, or a point that you wanted to make sure would come across?

MB: Hmm, no, the tricky parts didn’t really come about until we were actually sitting down and translating it. Before then, when reading it with our son, I was mostly focused on just reading it with him. I wasn’t thinking about how to translate it at that point.

The thing I really wanted to convey most was that kind of fantastical world, where anything could happen, and everything has agency in its own right. One thing I really wanted to focus on was that Sato was a part of the world, as opposed to controlling or owning anything from the world. In Sato’s world, everything could be its own agent, its own entity, like the pond that supplies water for Sato’s gardening, and I feel like that agency is what allows everything to exist as whatever it ends up being, however fantastical that may be. Sato wouldn’t own the pond or the walnuts or the watermelon in the stories; he would just be interacting with them and trying to keep them more as equals.

SB: I didn’t really think about translating when I was reading the books, but after that, when Michael was translating, I think the use of past tense and present tense was a tricky part. Because Sato often uses present tense, and we wondered: what world goes with the present tense? should we use the past tense for Sato’s world view?

I think the hardest part was to create the same world as the Japanese world in English. The book is also translated in French, and I read on Shogakukan’s blog, which is the Japanese publisher of the Sato books, that they had a story-time in Japanese and French for Sato, and the author said that the little differences in sounds and little differences in interactions and meanings between French and Japanese made it so that the feelings that readers got in the two languages were different. I think French seemed more direct, and Japanese seemed a little more soft. So, getting the Japanese softness into English is hard. I don’t know how to explain it, but it’s very hard to convey in English because it’s so different from the way that the Japanese would express it.

ERW: Can you share an example from the book where it felt very soft to you in Japanese, but maybe not as much in English?

MB: Sure. In “Walnuts,” Sato puts walnuts over his eyes, and it turns into a starry sky. When they talk about Sato covering his eyes with walnuts, the Japanese goes:

なかが ほらあなのようにくらい くるみが あったら、

こうして、 めに ふたを してみます。

A very literal translation of the Japanese text would say:

If there is a walnut whose inside is dark like a cave,

like this, (he) uses them as a cover on (his) eyes.

Japanese doesn’t include the subject, so we added “he,” and the second part sounds really awkward and clunky, so we changed that to be “he covers his eyes like this” in English.

The tricky thing is that “あったら” (attara), the expression at end of the first part, can mean “if” or “when” in Japanese depending on context. So when it came to the English, we were talking about if it was the first time he ever did that, or if it was something that happens repeatedly, because that would change how we would phrase it in the translation. We just can’t tell from the Japanese, but it would change whether I would use “if” or “when” for this sentence.

Is it every time he finds a walnut that’s as black as a cave, he does this? Or did he find one that was black as a cave, and so he intuitively knew to just put it over his eyes, because that’s what you do when you have walnuts that are black as a cave? Just based on the Japanese, I can’t know how often this happens, whether this is a common occurrence or not, and the English sentences we used maintain this vagueness: “The insides of one walnut are as dark as a cave. So he covers his eyes like this.”

SB: Yeah, “Walnuts” was a hard one. When you crack it open, is it every time? Or just sometimes? Does it suddenly happen, every once in a while? I don’t know, I can’t really tell! Is it something that you need to wish for?

MB: Yeah, it changes the whole concept of how walnuts exist in this world, and how much you can expect a walnut to contain some sort of magical experience, like hot coffee or a bath.

The sentence that comes right after, on the right-hand page, goes like this in the Japanese text:

はじめは まっくらやみでも、 しばらくするとー

(At first, it’s pitch black, but after a little while—)

This is followed by a page turn, and on the next page, it then says, if I’m translating very literally, “the sky becomes a starry night.”

I wanted to keep that tension with the page turn and describe the walnuts in the same way as in Japanese, so I translated the first part as “It’s pitch black at first” and used “after a little while” to maintain that build-up while keeping the same delivery of information as in the Japanese. There’s a construction in Japanese that’s a verb + と (to), which means that B happens once A has occurred, in that instant, and that’s what’s used at the end of this phrase, right before you turn the page. You can just say that without explaining, and it is what it is, and then you turn the page, and it turns into a starry sky.

Taking it all together, if we had done something like: “When he puts the walnuts to his eyes, it’s pitch black at first. But after a little while…”, I don’t think it would have worked as well with the layout of the images. Plus, I liked the idea of keeping shorter sentences.

SB: So much thought went into “Walnuts!”

ERW: And all that information wasn’t really explicit in the Japanese text, right? How did you think through what to do in English?

SB: I suppose it was talking to Claudia and the editorial side. We’d tell them our opinions, and they gave us all their opinions, so it’s not just our decisions.

MB: Yeah, I really appreciated working with Claudia and others at Enchanted Lion Books. We’ve been reading the Sato books for years and years, so talking with people who were experiencing it the first time and didn’t know what to expect and hadn’t had years of reading it to their child was very, very helpful. We were so familiar with it that fresh eyes really helped. Sometimes, we had to have the pictures for the visual assistance because they worked together, but I think taking just the words, and trying to see how much we could convey with just the words, was really helpful.

SB: I’m Japanese, and I understand the text clearly, but if somebody asks me why it is happening, I don’t know! Because I read it naturally, and I don’t need to think that much about it.

MB: I think one of our primary considerations with all this was that we were always keeping in mind how to create and maintain that world of fantasy, and imagination, and pretty much endless possibilities.

ERW: Something that struck me when I was reading Sato was that I feel like in American picture books, there is often a clear delimitation between the real world and the world of fantasy. It’s pretty common to go through a door or a portal or something to enter fantasyland, or just be in fairytale-land the whole time. But I feel like with Sato, he is very much interacting with things that are in our everyday world, but just in a fantastic way.

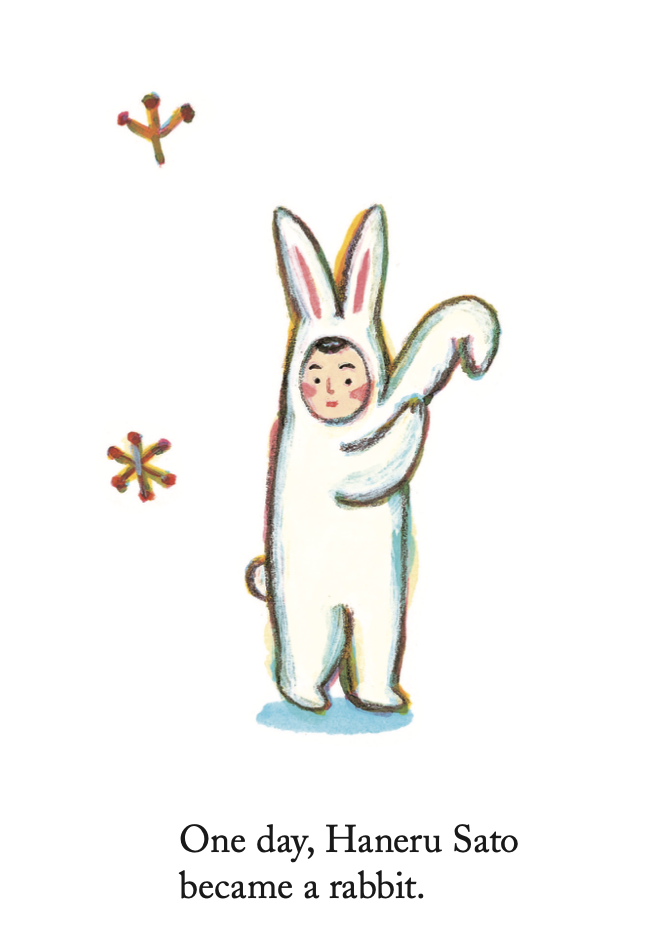

MB: Claudia and I also had a discussion pertaining to how much Sato intended to become a rabbit, whether or not he just became a rabbit one day. Was it an intentional decision, or was it just a happenstance occurrence? It starts out very simply, and then takes a hard right somewhere, and how much of that is Sato’s decision? In the end, it showed him putting on a costume, so I think we decided it was his decision, and he just kind of rolls with whatever happens.

ERW: Earlier, Shiz, you were saying that another big difference was the tense (present tense versus past tense). Can you tell me a little bit more about how you approached that, and what your decision was?

SB: It might be better for Michael to tell about that, because he was really going back and forth about using past tense and present tense.

MB: The Japanese goes back and forth between past and present tense and mixes them a lot, and in the end, it was an editorial decision with Claudia to put everything in the present tense, to keep everything in the moment.

ERW: Michael, you were saying that it was helpful to work with not just the text, that you’re also working with images. Can you share more about how images informed your translation process?

MB: Since each story is only about eight pages and it goes from point A to point L so quickly, there were a lot of times where the images and the words really worked together. There are a lot of page transitions where the surreal happens as the page turns. Like in “Watermelon,” he closes his eyes, and the taste of watermelon goes through his body, and then you turn the page, and he’s standing on the water, and the watermelon has become gigantic, and it’s floating on the sea. So, that interplay between the words and the images, I think, really helps make the surreal possible without having to over-explain what’s happening. The text can talk about how Sato feels or the reasons he’s doing something, and the images can convey how the world is changing around him, and Ainoya-san [the author and illustrator of the Sato books] doesn’t have to describe too much what’s happening in the words because the visuals supplement that.

ERW: That’s something that is unique about picture books: you’re not just reading a story told through words, you’re also reading it through images. Something else I find fascinating about picture books is that a lot of times, it’s something that’s being read to the child, or that the child is reading aloud. In translating, did you consider the sound, the pacing, the rhythm of the text?

MB: Oh, definitely. Thankfully, there weren’t too many sentences in each story, but for pretty much every sentence, I created a Word document, and for every noun and adjective and verb, I looked up every synonym I could, and then would create a sentence diagram. Essentially, I made the sentence, and then every place I could try to create a new way to phrase it, I wrote the sentence out that way.

And I definitely tried to put in alliteration and good rhythm. I didn’t really worry about rhymes, just because it didn’t feel like a rhyming book. I would be interested someday to do a children’s book and intentionally try to rhyme it, but it would take a lot—and finding the right book, too.

ERW: Do you feel like Japanese children’s books focus on rhythm and sounds, and the read-aloud quality of a book, too?

SB: Not as much as English books. English books really care about that. Even for me, who knows English as a second language, I feel that sometimes a book doesn’t really rhyme well. When English children’s books don’t rhyme well, it really feels strange to read, and it’s really hard to read.

MB: Or when all the book rhymes, except there’s one part that doesn’t rhyme.

SB: In Japanese books, I don’t feel that way as much. Of course, rhythm is important, but I don’t think it’s as important as in English books.

ERW: Is that because of different cultural expectations in how children’s books are read? In the United States, I feel like it’s often the parent, or the teacher, or the caretaker reading to the child with picture books. How are picture books read in Japan?

MB: Well, we always read before bed, but do you think most Japanese parents do that, Shiz?

SB: It really depends on the family. Reading books is becoming more important for educational reasons, I suppose. I don’t know, I feel like we don’t have many samples, but compared to my Japanese friends, my American friends read more to their children… But I feel like it really depends on the family.

MB: Maybe we’re just not around when they are usually reading.

SB: We read a lot more to our son, I think, compared to our friends. Personally, I think even though children can read by themselves, it’s better for parents or another adult to read for them, so that they can focus on the pictures more than on the text. It happens to me, too: when I’m watching movies, if there are captions, I always follow the subtitles, and I don’t really look at the full visuals of the movie. I think children’s books should focus on the pictures. The story is important, too, but it’s a picture book, so kids should look at the pictures more than the text, at least until a certain age.

ERW: Or at least make sure that they’re looking at both, not just the text. Because so much storytelling happens through the pictures!

Want to read more about Sato the Rabbit and Michael and Shizuka Blaskowsky’s translation? Part two of the interview is up on our blog here!

Interested in learning even more about the art of translating children’s literature? Don’t forget to join Michael and Shiz, in conversation with Enchanted Lion, in a live Crowdcast event happening Sunday, March 7, 4–5 pm ET (tickets available here)!