Part 2: A Conversation with Michael and Shizuka Blaskowsky, the Translator Team behind SATO THE RABBIT

Even the most routine activities transform into magical adventures in Yuki Ainoya’s Sato the Rabbit, the first picture book in a trilogy from Japan. Michael and Shizuka Blaskowsky, the husband-and-wife team who translated Sato into English, speak with Enchanted Lion’s Emilie Robert Wong about the differences between American and Japanese storybooks, the immersive power of illustrations, and the endless possibilities of Sato’s dreamlike and fantastical world. This is the second and final part of the interview, which took place on October 29, 2020 (read part one here).

Want to learn more about the whimsical Sato the Rabbit series and the art of translating children’s literature? Join Michael and Shiz, in conversation with Enchanted Lion, in a live Crowdcast event happening Sunday, March 7, 4–5 pm ET (tickets available here)!

ERW: Would you tell us a little bit more about your translation process? You mentioned at the beginning of this interview that since you’ve been doing it for a while together, you have a routine.

MB: Usually, I’ll do the first translation and really focus on trying to convey the meaning behind it and make sure that it makes sense in English. And then Shiz will read through it. Shiz, what do you focus on in the first read-through, assuming we’re doing more than one?

SB: In the first read-through, I focus on the meaning. The goal is for all the meaning that the Japanese has, to be there in English. And sometimes, it’s not really the right word for the Japanese, so to point that out, too. But of course, I could be wrong, so we talk together, and we discuss whether it’s right for the original sentence.

MB: When I'm translating, it’s nice to know that if there’s a part I don’t quite understand—I mean, obviously we live together—I can just turn around and ask her at those points. If there’s something I don’t quite get, I can give it my best shot and make a note that I think we need to talk about this part, that I don’t quite feel 100 percent that this is where it needs to be. Usually, those turn into one- or two-minute conversations, and then we end up spending five minutes over a three-word sentence that we both thought was going to be really easy—but that’s always the surprise that we never know about!

And then, as we talk, I’ll rewrite the sentence, and when we come to something that we agree on as far as the meaning being there, I’ll take it back and try to make more interesting and engaging English sentences, while trying to preserve that meaning that we discussed. Then when I feel like that’s pretty good, Shiz will take it over again, and that’s when she gets really nit-picky—in a good way, it makes her a good proofreader!

SB: The second time, I focus on other things that I miss during the first reading. And sometimes, we have to go back to get the meaning because in the second round, he changes the wording to make it sound more natural, and that sometimes makes the sentence stray a little far from the original sentence. So I try to address that.

MB: The second write-through is definitely when I’ll write a sentence and sometimes think, “Ah! She’s going to want to talk to me about this.” I just want to try to localize it and make it sound more natural and smoother, while still trying to retain and convey what the Japanese is trying to convey, in the way it tries to convey it. Style especially can start getting separated at this stage, so the second read-through helps anchor that.

Then once we’re good on the meanings and the nuance, making sure everything is conveyed well, I’ll usually give it one or two more read-throughs, just to take it as an entire document, with less reference to the Japanese that time. Generally, I know where the problem areas are, or places where I’ve wanted to stray a little bit further from the Japanese than maybe is nice, so I know to take special care with those sections. I try to treat it as almost an English document or story or text, and make sure that it makes sense, that it flows well, that it sounds nice. Just little tweaks at the end, essentially.

SB: That’s the good thing about working as a team, because if I do it just by myself, of course it’s not going to be really natural in English. I tend to stay too close to the original, but at the end, the translation should be more natural for the English speakers. Sometimes I get too nit-picky, because it doesn’t sound like the original sentence, but the meaning is right, so we have to discuss that.

MB: And I have to say, as a group, I think we stay very, very close to the original Japanese versus other translators. I’ve seen some examples that—I mean, I’m not saying they’re wrong or bad, they’re definitely good translations, but I’ve looked at them, and thought, “Oh, wow, they really took some liberties there.”

Especially talking with other translators of literature, people who work with short stories, novels, things like that, I’ve had a couple translators essentially say they almost treat the English like a different work itself. I was in a conference where the translator worked very closely with the Japanese author throughout the process, but the Japanese author said the English is a different work itself: it’s not a translation, it is a work of literature in its own right. So, that’s a lot of freedom!

One really nice thing to do is to read an English text alongside the Japanese source, and people have said, “Do that, and you’ll see how much you can get away with as a translator that still works.” Because at the end, if we stay really close to the Japanese, but it doesn’t make any sense to an English audience… The English audience doesn’t know anything about the Japanese source, so in the end, it has to make sense as an English story.

But we personally feel like we should stay as close to the Japanese as we can. Because we’re not the authors, we’re not the creators of this world, we’re just the middle-people who help relay it to other people who don’t understand Japanese. So, I think we don’t take so many liberties because we’re not the creators of said world or text, and Ainoya-san is the one who decided what information to exclude or not, or include or not include, in each one of the stories, and we want to make sure that we honor that.

ERW: We’ve already touched on this a bit, but how would you describe your goal as a translator? What does a faithful translation look like to you?

MB: I’m going to stick to the literature world here, because it’s so radically different, and it really depends on what you’re translating. If it’s a user manual, there’s a lot less to consider. I would say as a translator of literature, I think it’s most important to understand why the author created that work and what kind of characters and atmosphere they’re trying to convey, and try to bring that into English. Hemingway is really famous for short sentences, and if you were to translate Hemingway into Spanish and you just started combining sentences together, you would lose what Hemingway is famous for. I think you need to honor the style that the author is known for. I think you do have the freedom as a translator to in that example, divide or combine sentences here or there to make it more accessible for the readers. But still, I think as a translator, if an author is trying to create a certain mood or persona for a character, that it’s important to convey that. Because they could have done literally anything: they had a blank piece of paper, and they decided to put certain words on it for certain reasons.

SB: My work is mostly proofreading, not translating, so it’s different. I pick out the wrong word or the wrong sentence, and tell Michael. Ideally, for one Japanese word, we could get, without a dictionary, six or so more English words. How about that word, that word, that word, that word, for this Japanese word? It’s different from translation, but we need that additional vocabulary to make better translations. The translator has to have the best possible understanding of the words.

ERW: You were just sharing that you wanted to really capture the author’s style and bring that to the English-language audience. How would you describe the style of Sato?

MB: Hmm, a lot of the words the three of us have used so far, I think: fantastical, surreal, dreamy, full of opportunity and adventure… Because the words are there to work with the pictures, the text didn’t need to be so descriptive. There needed to be some descriptions of what’s happening to move the story along, but I really liked that in the Japanese, there was a lot that was open for play. I wanted to keep that idea of anything being possible in it.

SB: I guess, the feeling of fantasy. You know it’s never going to happen in our world, but I can see it happening in Sato’s world, and I wish it could actually happen for us. It’s not in this book [Sato the Rabbit], but in its follow-up [book 2, Sato the Rabbit: The Moon]: there’s a reflection of the moon on a pond, and Sato can actually grab that reflection and eat it, and it’s nice and cold and tasty. I want to do that! I know it’s not going to happen, but it happens in Sato’s world.

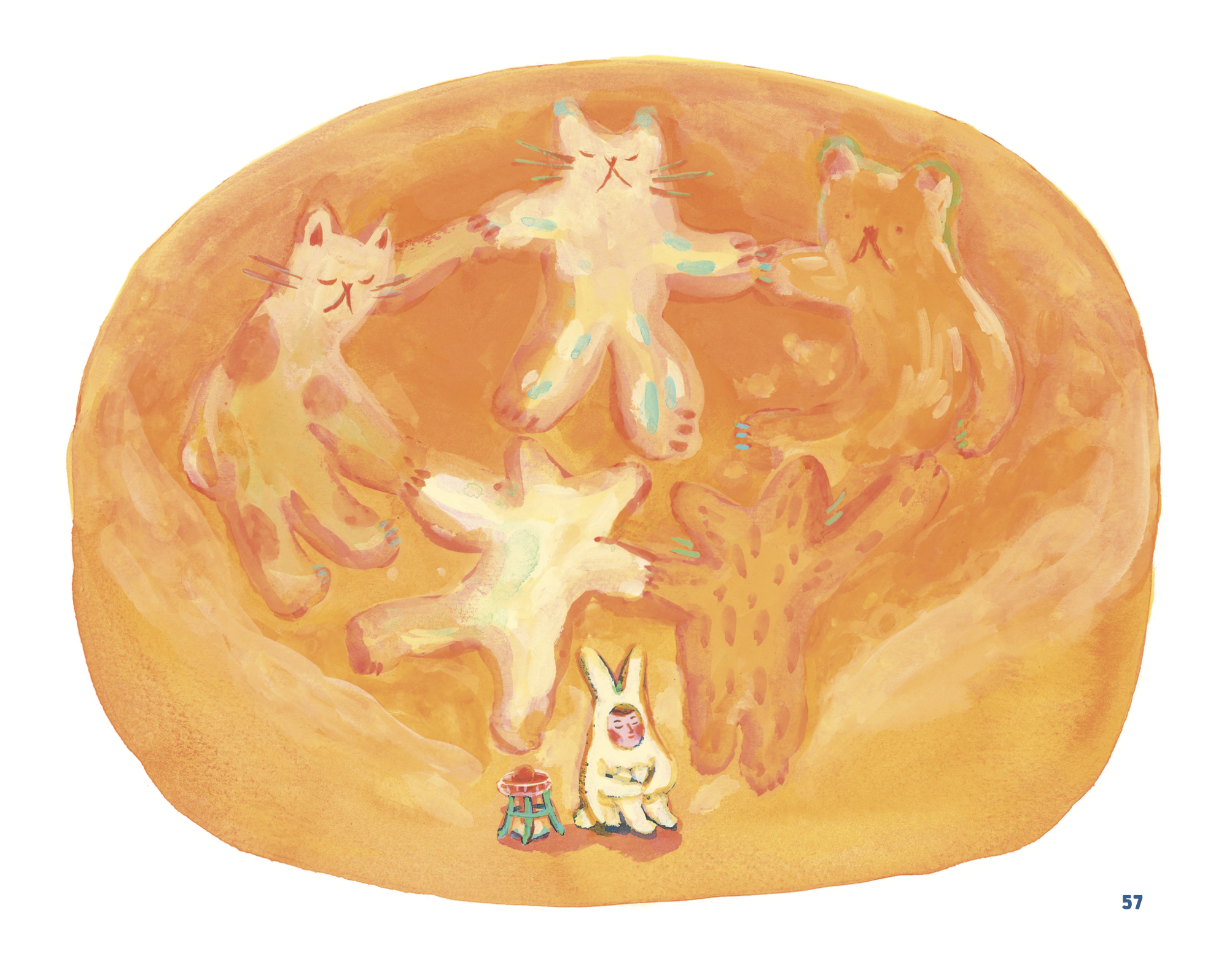

MB: I got a lot of information and inspiration for the atmosphere from the pictures, actually. The style of the pictures being done in watercolor is really essential to create that soft-edge world that Sato lives in. I don’t think you could do it—it would just be so different if it were all pencils or acrylic paint. They’re just so much harder and more sharply defined. The watercolors are dreamy, and it makes things transition into each other a lot easier. Even the way that a tree would sit on a snowy field, the transition into itself is a lot smoother and mixed together in a way that I don’t think you could do if it were pencil or paint. So, I get a lot of inspiration for the kind of atmosphere to create from the pictures.

SB: Ainoya-san does a lot of work in picture books, and her style is really soft and nice, pastel and dreamy, not aggressive at all. We really like that art style a lot.

ERW: I saw on your website that you translate video games, literature, and more technical business documents. To what extent would you say that translating Sato, as a picture book specifically, is different from the other things that you translate?

MB: Oh, it’s very, very different. I would say the general process is the same, in that I translate, Shiz checks, and we talk, and then we repeat as needed. But for Sato, there was a lot more revision and talking and more involved discussions over specific words. I think literature requires that because there’s always a meaning of things unsaid, so you have to be very specific with your words. Whereas for a legal document, you have to be very specific with your words, but that’s because each one has a very defined meaning in a legal sense, and you’re translating that and thinking, “Someone could get sued over this. I have to make sure it’s the right word.” Hopefully, no one sues anybody over Sato, going on a watermelon boat or something!

SB: Wording for children is something to consider, too, so that it’s easier to understand—not too challenging, but not too easy—as well as getting the right meaning from the Japanese. So, it was really different from the other work we do, as our first picture book.

MB: Having the pictures was really helpful. The video game work we do—it’s odd because video games also have a very strong visual component to them, but we’ve never been supplied with visuals for any of that. It’s all text, and it’s all trying to create the world and convey the characters from text—when we might not even know what they look like, so we don’t know how rough this person should be speaking. But it was much more complete with Sato.

As Shiz mentioned, we were very careful about word choice to make sure that the right age range can understand and appreciate it, from five to ten, or whatever the audience is that’s going to be most involved in the book. I used “melancholy” as a term, because I’ve seen English children’s books throw in some pretty complicated words every now and then. Maybe that’s more common in modern picture books, to every now and then throw in a really big word for kids—and this is just speculation—so that they are discovering new words early. They may not know what the words mean, and it may just land on their ear and they don’t ask their parents about it, but at least they hear it. Maybe there’s one or two of those kinds of words snuck into a picture book.

ERW: Did you end up keeping “melancholy” in the translation for Sato, or did you go with a different word?

MB: No, we changed it to sadness, just to make it more accessible. In the end, we decided “sad” was just more relatable to kids, where they would intimately know sadness and could associate with what was happening in the book better. And if you’re trying to get kids to follow Sato on this fantastical journey, it does kind of break the world if on page six, the parent sits there and explains what melancholy is.

ERW: To what extent would you consider this translation to be different from the original text? Do you think anything has been lost or limited by the English? Or maybe something has been added, where English happened to be well-suited to amplifying a certain aspect of the text?

SB: I think it’s pretty close to the original, even though it’s very natural in English and very interesting. What is lost or added… Maybe Michael has a better answer? I think we got all the important parts.

MB: I think we got the main atmosphere. I hope the atmosphere was conveyed. I think the world that readers are invited into was successfully reproduced.

As far as things lost, Japanese has a lot of onomatopoeic sounds that had to be either completely left behind or changed into a verb in a sentence. I’m trying to think of some of those in the first book; she tends to add more in the second and third books. This won’t be from the first book, but there’s one moment where Sato has his head underwater, and basically, it’s “コポコポ” (kopokopo), the sound of a spring burbling underwater. And you can’t really put that in. We could do something like, “Bubble-bubble-bubble. He hears the sound of the water,” but it doesn’t quite have the same ring to it. It sounds really forced in English to try to have every single onomatopoeic sound included, so you just have to let it go.

Here’s a good example. In “Sea of Grass,” we worked the sound in there, but it was something like: “Whoosh! A perfect gust of wind arrives.” That sound has to live on its own, whereas in Japanese, it’s worked into the sentence a lot more easily and smoothly.

There are instances where we just had to not include the sound itself, and maybe find a more playful or entertaining verb to help convey that. I do think that’s one thing that doesn’t quite get conveyed from the Japanese, just because the Japanese use those sounds so much more often, and it’s really hard to bring that over into English. A lot of manga translators have that problem, but at least there are those standalone “Bam!” or “Piff!” bubbles, as opposed to working them into a sentence.

And then as Shiz mentioned, as far as things added, there’s not so much rhyming in Japanese, and I haven’t noticed, although this could just be me, a lot of things like alliteration. And that was something I tried to put in a lot, but only as when possible, in Sato, to add a playful tone to it. So that’s one thing that was maybe added, a minor thing but still added, to the English.

ERW: There’s an oft-quoted figure that only three percent of the books published in the United States are works in translation. Why do you think it’s important to read translations?

MB: Actually, when I was researching ELB to get a better understanding of the publisher we’d approached, I read an interview with Claudia when she was talking about Latin American authors that she was working with (I think the author in question was from Mexico). She mentioned that in the author’s country, there’s the idea that children’s books don’t necessarily have to be happy or have happy endings as much as in the States and in English. In American books, there’s always resolution: the main character always, always prevails in the end, and everybody always has the fairytale ending. But that’s very unrealistic! And I do feel like you shouldn’t squash children’s dreams, but at the same time, they see reality, and they see life. And they should be exposed to not necessarily sad moments, but maybe not fantastic, happy, fairytale endings, either. Just normal endings are okay. So, I think the idea of a different style and different cultural expectations from what they know are good things to expose them to as they read works from other countries.

SB: Yes, when you read books from other countries, you have access to different lives, different worlds, different cultures. And reading about those things in a language that you know, to understand other cultures, is definitely an advantage to translation.

ERW: What do you hope that English-speaking readers will get out of Sato? (A mood, a feeling, a different perspective?)

SB: I hope they enjoy the fantasy world of Sato. I really enjoy that things that are totally unreal and unexpected happen in Sato, and I purely want them to enjoy it, too.

MB: Yeah, I hope that people connect and enjoy Sato to the extent that we have.

ERW: Great, do you have anything else you’d like to add before we move on to ELB’s Ten Questions?

MB: One additional thing about why it’s important to read books from other cultures, or translated from other languages. I was listening to a podcast about the most checked-out books recently, and there was this whole story about why Goodnight Moon was not on the list. Seven out of ten, or six out of ten, of the most checked-out books are children’s books. And there was a little note that Goodnight Moon was not on there, even though it’s a quintessential children’s book, because the buyer for the New York Public Library for something like twenty years had a certain agenda and a certain idea about what children’s books should be. She kept Goodnight Moon out of New York Public Library shelves for ten or fifteen years, and even when she retired, she worked to make sure that Goodnight Moon, and other books that were more about the everyday, were kept off of shelves.

To draw maybe not the best parallel in the world: in our culture, we are given certain ideas about what should constitute a good children’s book story, but maybe there’s something like Goodnight Moon out there that really does resonate with children well, that another culture emphasizes more. And by reading books from different cultures, maybe you find different aspects of life that you connect with that just aren’t emphasized as much in English books.

SB: The translation is going the other way around, but in Japan, there are a lot of English books translated in Japanese. And what I found interesting was that there was a book translated into the Osaka dialect, which is a dialect that’s really strong that’s used in Japan. It’s definitely not regular Japanese, it’s not standard Japanese, but you can play with those kinds of things when you are translating books. And that’s a really fun thing about translation!

And now… Enchanted Lion’s Ten Questions

1. What is your favorite word?

MB: In Japanese, I really like “そろそろ” (sorosoro). I just think it sounds nice. It means “pretty soon”: when something is just about to happen, when you’re going to do something, it’s “そろそろ” (sorosoro). I like “perfunctory” as an English word; I just think it sounds neat.

SB: Wow, I can’t really think of anything. In Japanese, I really like those onomatopoeias we were talking about.

2. What is your least favorite word?

MB: I’m one of those people that has that weird cringe when they hear the word “moist.”

SB: I don’t like words that are really hard to pronounce. I really hate to say them.

3. Do you have any real-life heroes?

MB: I don’t know, there are a lot of people I look up to. Basically, anybody that works hard. Nothing really comes to mind…

SB: My grandmother.

4. What natural gift other than those that you have would you most like to possess?

MB: I’d like to have a really good tongue, to be able to taste things really delicately, really intimately. To really taste a dish and savor it very well.

SB: I want a photographic memory.

MB: Actually, I don’t know if it’s known as a natural gift, but I would like synesthesia, where everything has a color and you see patterns in everything.

5. What is your life motto?

SB: Work less, have more fun.

MB: You might as well just try. Or it never hurts to ask.

6. What is your idea of success?

MB: Being content with where I am and the trajectory of where I’m at, at more or less all times.

SB: Die smiling!

7. Are rituals part of your creative process?

SB: After work, eating sweets.

MB: I always have music on when I’m translating.

8. What does procrastination look like for you?

MB: Cleaning. I clean a lot when I’m procrastinating.

SB: Studying. Rearranging the furniture, organizing the things that I don’t need to organize.

9. How would you describe your monsters?

MB: Self-doubt.

SB: The hidden anger deep inside me that pops out every now and then. That’s a childish part of me, I guess.

10. What does earthly happiness look like to you?

MB: Doing the things that bring fulfillment and enjoyment to yourself.

SB: Looking out the window, and it’s raining, and we don’t have to go outside. There are so many… Recently, I was sitting outside, looking up and just watching the crowd moving by—that was happiness.

ERW: That sounds like the beginning of a Sato adventure.

SB: I was actually thinking about that: Sato would do something with that crowd.

MB: It’s surprising the number of times that we can reference Sato.

ERW: It’s a rich text!

If you missed part one of the interview, you can read it here.

Want to learn even more about the whimsical Sato the Rabbit series and the art of translating children’s literature? Join Michael and Shiz, in conversation with Enchanted Lion, in a live Crowdcast event happening Sunday, March 7, 4–5 pm ET (tickets available here)!