A Conversation with Valerio Vidali, Illustrator of TELEPHONE TALES

In this interview, Enchanted Lion’s Emma Vitoria talks with Valerio Vidali, illustrator of Enchanted Lion’s edition of Gianni Rodari’s Telephone Tales. Their conversation spans the unique challenge of illustrating the words of an author as iconic as Rodari (particularly in Vidali’s native Italy), the importance of play in artistic practice, and an early concept for illustrating the book that was ultimately left behind, but was integral in arriving at the final artwork.

EV: Having grown up in Italy, can you introduce us to any Italian children’s books that were an important part of your childhood? Do you find any big differences between Italian picture books and American ones?

VV: This might sound a little sad, but I didn't have access to picture books when I was a child, although I did have a beautifully illustrated encyclopedia that I devoured with my eyes, and also a collection of literature classics, like Tom Sawyer, Huckleberry Finn, Hans Brinker: or, The Silver Skates, Robin Hood, The Prince and the Pauper and The Paul Street Boys.

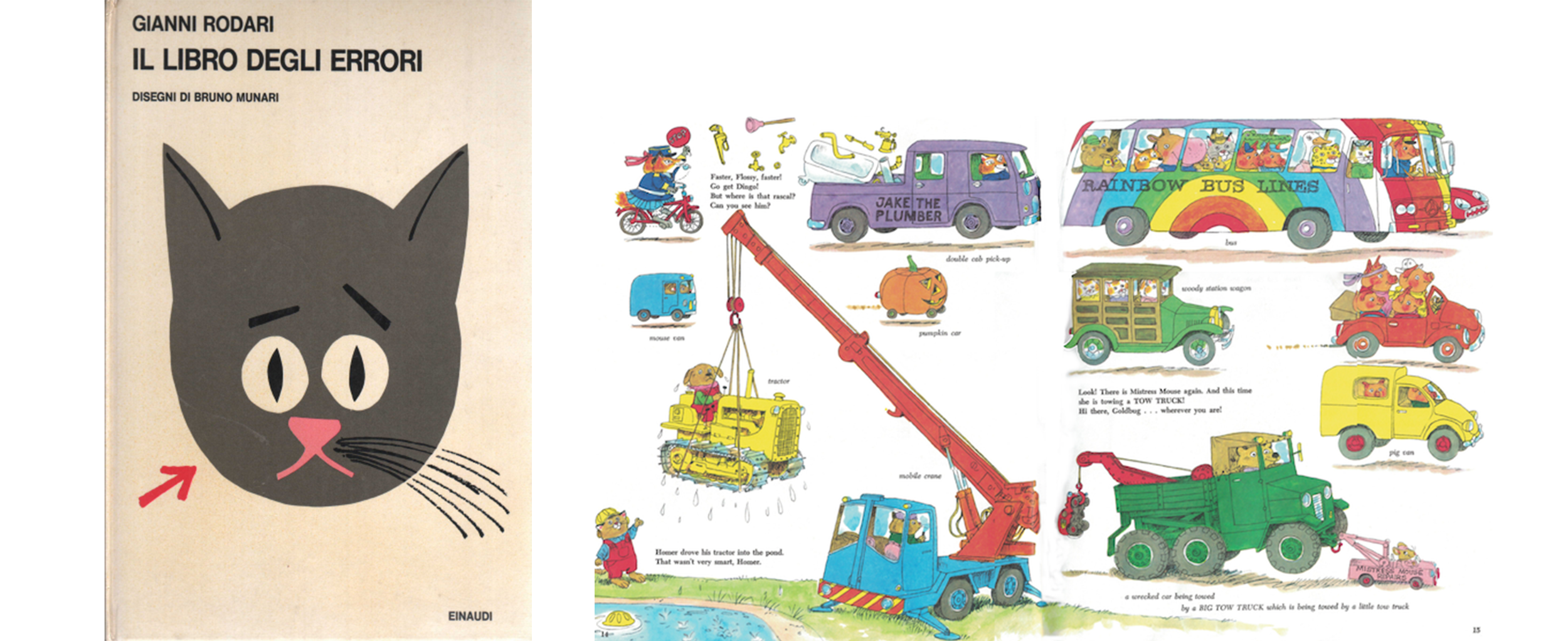

The Italian author par excellence, of course, was Gianni Rodari. My favorites were The Book of Mistakes and Telephone Tales.

The only picture book I grew up with was a really big book by Richard Scarry, that I still love and treasure.

EV: When you think back to some of your favorite childhood books, do you notice any ways that they have stayed with you, influencing your own approach to illustration, bookmaking, and storytelling?

VV: Both the illustrated encyclopedia and the Richard Scarry picture book taught me the pleasure of crowded images and the joy of discovering little details. I believe this is something I still carry on with in my work, sometimes up to a detrimental point.

Simplicity is often the best way to go, and my natural instinct to fill the image with details makes it harder for me to achieve it.

EV: Do you see any traits from your childhood-artist-self that have endured? Or, are there any traits from your childhood-art-making that you find yourself trying to get back to in your professional work?

VV: Being an illustrator can be grueling. The daily routine, the stress of an approaching deadline, the creative blocks. The road to a satisfying final result is often long and bumpy. When I get frustrated and lost during the process, remembering how I felt as a child while drawing is a big help, it takes me back to the basics, which is having fun.

EV: As an Italian, can you describe the impact that Gianni Rodari’s work—Favole al Telefono, or others—on you? How do you feel about having illustrated the stories of such a prominent Italian author for a whole new audience?○The original version of this book was published in 1962 by Einaudi Editore, featuring illustrations by Bruno Munari that are quite different and more minimal than your own. Is this the version you grew up with? Do you remember imagining any of your own pictures to accompany the stories when you read this book as a child, and did any of these childhood images stick with you when making the art for the English edition?

VV: Rodari's work and creativity can be found everywhere in Italy, it's embedded in the work of educators and in the school system itself.

Rodari is the first name that comes to my mind when I think about children's literature, and illustrating a book I loved as a child for a whole new audience has been a treat and an absolute privilege.

I grew up with the edition illustrated by Bruno Munari, yes!

He is, of course, the godfather of many Italian illustrators and designers and a great source of inspiration (the cover of C'era Due Volte il Barone Lamberto might be the best drawing ever made if you ask me :) )

EV: Please tell us a little bit about how you came to work on Telephone Tales with Enchanted Lion. What were some of your early feelings about this project?

VV: If I remember correctly, I was having lunch with Claudia. She was telling me that she managed to acquire the English rights of Telephone Tales and she was very excited about it. She also told me she didn't have an illustrator for it yet, and she asked me: "Do you have anybody in mind that you think could do a good job illustrating Rodari?" and I (very selfishly) replied: "ME!! I would do a good job!”

My early feelings were a lot of excitement and a little concern.

As a reader, Telephone Tales has a big sentimental value for me, but having already illustrated Rodari once in the past, (Novelle Fatte a Macchina, Einaudi 2011) I know that Rodari can be tricky to illustrate. His writing is so rich and surreal that often, an illustration is not necessary .

On top of that, Telephone Tales is a big book and quite a bit of work.

EV: The books you’ve illustrated range greatly in text, from a collection of stories like Telephone Tales with much more elaborate & descriptive text to a book like Hundred, with much more minimal text. Does your approach to the illustrations and the imaginative process change, depending on how much detail is contained in the text? What do you think about the relationship between your images, and what exists in words?

VV: A less descriptive text gives me more freedom of interpretation, as I can decide to use visual metaphors or to work in a more narrative way.

Very descriptive writing is much more restraining, you can still be creative but you have to find your way around the text.

EV: How much play and exploration are involved in realizing the final art for your books? Do your experiments ever become a part of the final result? Or is it a separate phase of the process altogether? Is there anything you explored (idea, composition, medium...) during your creative process that didn’t make its way into the final book (can apply to Telephone Tales or The Shadow Elephant!), but that you’re glad to have spent the time exploring anyway?

VV: There is always a phase of experimentation at the beginning, in the case of Telephone Tales my early idea was to illustrate the book using exclusively office supplies (Bic pens, Mechanical pencils, cheap markers, and such) with a style that would resemble the doodles people make on doodle pads while talking on a landline phone. I worked on this idea for quite some time, I liked this concept very much but in the end, I decided to take a different direction for a couple of reasons: drawing using office supply proved to be quite unpleasant and frustrating, and more importantly, I was worried that the "doodle" aesthetic would make the book look a bit bland and uninteresting to the young readers.

For these reasons, the final artwork was realized using mostly ink-filled water brushes and markers (these are the tools I usually use to doodle and sketch in my notebook, so in a way, the illustrations are a fancy version of the normal doodling I do in the studio).

From Telephone Tales.

In the case of The Shadow Elephant, there was very little experimentation. At the time, I was traveling in Colombia and bringing paintbrushes and paper along with me wasn’t practical, so I brought an iPad instead.

In the beginning, I intended to use the iPad to work only on the storyboard and narrative, (and later paint the artwork analogically) but I was so pleased by the digital result that I decided to work directly on the final artwork. Everything happened very quickly and organically in just a few weeks. This was the first time I illustrated a book digitally.

From The Shadow Elephant, written by Nadine Robert.

EV: Your books convey stories from a wide range of emotional perspectives and life experiences. The journey through life to old age is a recurring theme in The Forest and Hundred, and The Shadow Elephant explores some very difficult emotions. Can you tell us about what it’s like to illustrate these topics and experiences? What kind of sensitivity do you find is involved, and how do you tap into that empathy?○ Does illustrating these experiences ever teach you new things about yourself, or give you new understandings of the people in your life?

VV: Working on books that explore complex topics and feelings gives me the opportunity to think more deeply about a certain topic, and developing a more educated opinion about it. The Shadow Elephant, for example, made me reflect on what sadness is, the stigma that carries, and how our society deals with it like it is a problem that needs to be fixed. Sadness is a human emotion like any other:a little chemistry-magic that happens in our brains. It often needs comprehension more than it needs a solution.

EV: Can you share a bit on how you go about approaching each new story you work on? What informs your decisions in terms of process, medium, etc? For the art in Telephone Tales, in particular, you arrived at a concept inspired by the old corded-telephone “doodle pad”, and the act of doodling itself. How did you arrive at this idea? Was it through conversation, experimentation, or just a sudden flash of inspiration? Can you tell us about how this approach lent itself to the gatefolds and small inserts of the book?

VV: After I let go of the idea of "doodle pad" aesthetics, I thought that the best way to approach the work would be to try to match the playfulness and surrealism of Rodari's writing by making the illustrations and the layout as playful and fun as possible. For this reason, there is no real structure in the layout. The illustrations appear in different shape and form (single page, spot, gatefolds, spreads and tiny glued inserts of different sizes).

I used water-brushes and markers because I wanted the working process to be quick and fun too, just like when I draw in my notebooks.

EV: One of the most significant aspects that make each of your books unique is the strong use of color, and an often limited palette. How do you go about creating a color palette for a new book? What influences your decisions?

VV: Color always contains a communicative function, so it has to be used accordingly.

In The Shadow Elephant, the Elephant is living in a blue on blue space/reality, with the blue color, in this case, portraying the Elephant’s apathy and sadness.

In Jemmy Button, the jungle is painted in a lush and vibrant green, while the city is realized with a more graphical collage of white/gray papers. The people that live in the city are depicted as blue silhouettes while Jemmy Button, being an outsider, is full of color.

In The Forest, we did something similar, with Nature depicted in vibrant and luminous colors while the people exploring it are embossed on the white pages. This is a metaphor of our human tendency of seeing ourselves as autonomous beings, growing apart from nature.

The use of a reduced color palette is usually an aesthetic decision, but it can also have a function.The fewer the colors, the stronger is the meaning they carry.

EV: Pacing is another significant element in your books. How do you approach the feeling of time or transition visually?

VV: I generally like to create images that evoke a feeling of stillness, a sort of meditative calm.

Every image has a "time length " component in it, which varies depending on the story and what I'm trying to communicate. In the case of The Shadow Elephant, the passing of time is figuratively represented, as we can see the sun moving in the background and the light changing color in every page. Every scene is presented in a very theatrical way, with the characters placed at the center of the scene while the background is constantly changing. The depiction of time passing is very important for the story. Sadness is a lingering feeling,and doesn't go away from one minute to the next; it takes time.

EV: Please tell us more about your early experiences as an illustrator. Did you study art or design in school? If so, did your education ever involve collaborative projects, or was it primarily individual work? Do you find that your education prepared you for your professional life?

VV: I studied Illustration in Milan; it never involved collaborative projects but I met some wonderful people there. I don't think they prepared me for my professional life, but they certainly took me a few steps further towards a career.

I had some good teachers and some bad ones like anybody else. More importantly, I would say that I was lucky to have some very classmates.

EV: Some of your books are the fruit of beautiful collaborations with other talented artists, like Jennifer Uman (Jemmy Button), and Violeta Lópiz (The Forest). What are some of the biggest challenges and rewards of collaboration, for you? Do you have any advice for other illustrators who are new to collaboration and learning how to navigate it for themselves?

VV: Collaborating with other artists has been a beautiful and fulfilling experience, just as it’s been very hard and frustrating at times. In collaboration, there are many more aspects involved than just creativity: there’s tons of communication, the aspect of personal relations, insecurities, and ego clash. It's a crazy rollercoaster, but it’s also wonderful. There is so much to be learned from other people, and I feel lucky to have had such experiences. Illustrating is a lonely profession and I hope to have more collaboration in the future. I definitely recommend it to other artists.

EV: What are some of your hobbies, interests, or favorite things to do aside from art?

VV: Over the last few years, I've been more and more interested in sculpture.

I'm currently learning hand woodworking and hopefully, one day, I will be able to build my own furniture.

EV: How, when, and why did you get into children’s illustration?

VV: In Italy, the mainstream idea of art is what you can see in churches and museums. I grew up drawing saints and virgins. I wanted to be a painter but I didn't know how. The fine art academy in Milan looked like a wonderful place from the outside, but the whole art world seemed far-fetched to me (it still does). Illustration sounded more reasonable, and more like a tangible profession. I didn't know much about it when I applied to the school, but soon afterwards, I fell in love with it.

EV: What, if anything, do you like to listen to while you work (podcasts, music type, etc). Does this change depending on the stage of the process, or the energy of the project?

VV: While working, instead of music, I like to listen to movies, usually movies that I've already seen, and they either have a beautiful soundtrack or plenty of good dialogue.

EV: Art is an endless journey of self-improvement and transcendence. What are your strengths as an artist? Your weaknesses? And where are you interested in going as regards further exploration and discovery?

VV: I'm very patient, but also terribly lazy. I would love to have more skills, in general. I would like to learn craftsmanship like welding, carpentry, or ceramics. Next month, I will be traveling to a small town in central Portugal to participate in a blacksmith workshop. Here in Portugal, there is also a beautiful, centuries-long tradition of tile painting, and I would like to learn that too. maybe even make a book with it at some point. In the future, I would like my work to have a more interdisciplinary aspect.

10 ELB Questions (asked in every interview!)

1. What is your favorite word? "Ojalà", is a Spanish word that literally means "God willing"

(it derives from the Arabic "Inshallah" ) but is colloquially used regardless of the speaker's faith as a sort of "I hope so.."

2. What is your least favorite word? "cute"

3. Who, living or dead, inspires you in your life? Bruno Munari, Leo Lionni, Enzo Mari. Sweet people.

4. What natural gift, other than what you have, would you most like to possess? I wish I was more stubborn. Sometimes I get demoralized easily

5. Do you have a life motto? Not really. "Fail more, fail better"?

6. What is your idea of success? A veggie garden in the sunshine

7. Are rituals part of your creative process? I don't have rituals, but I for sure have some repeating routines;

morning coffee followed by some procrastination and some mail reading, a little walk to the studio, more procrastination, lunch, few hours of productive work, more coffee, more procrastination, and some mail answering. Then a walk home.

8. What does procrastination look like for you?

Procrastination is a giant part of my day.

I choose to believe that procrastination is a fundamental part of the creative process, although I'm not really sure of it. I may be lying to myself.

9. How would you describe your monsters?

Sometimes I choose to not face the issues (the monsters).

and that choice is the real monster.

10. What is your idea of earthly happiness? I'm sticking with a veggie garden in the sunshine.