Part 1: A Conversation with the Author & Illustrator of SNOOZIE, SUNNY, AND SO-SO

In Snoozie, Sunny, and So-So, a timid dog who has been feeling “so-so” for quite some time has a life-changing chance encounter with a pair of best friends, a cat who doesn’t like moving and a dog who’s afraid of the rain. This gorgeously illustrated chapter book tells a moving tale of finding support and joy in close friendships and opening yourself up again to face new adventures.

Touching on loss and childhood, poetry and color, and Maurice Sendak and animal companions, author Dafna Ben-Zvi and illustrator Ofra Amit speak with Enchanted Lion’s Emilie Robert Wong about how Snoozie, Sunny, and So-So came to be. In part one of the interview, which took place on December 31, 2020, Ofra and Dafna discuss the theme of moving on from loss, how music and emotion drive their creative processes, and the real-life pets that inspired Snoozie, Sunny, and So-So. (Read part two on our blog here!)

The moment right before Sunny and Snoozie meet So-So

ERW: Taking it back to the beginning, how did the idea for Snoozie, Sunny, and So-So first come to you?

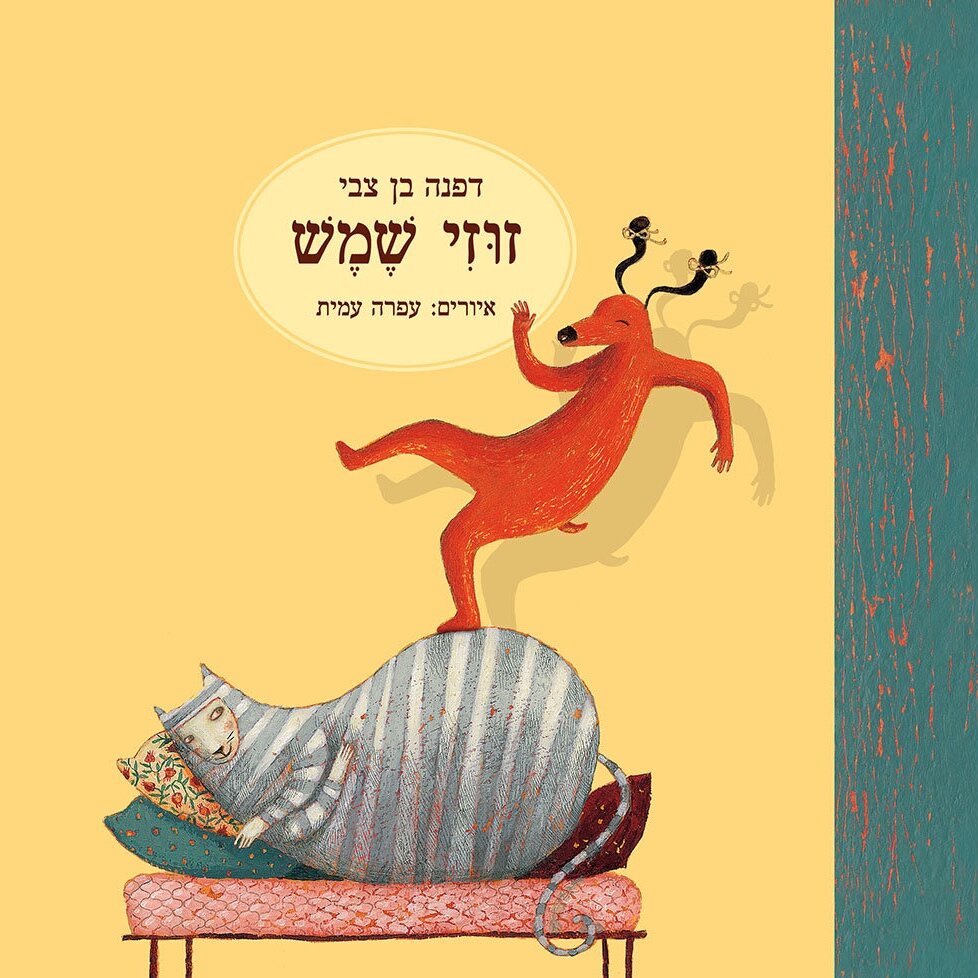

DBZ: Well, it’s actually the second book in a series. The first book, Sunny and Snoozie (Zuzi Shemesh), is a short picture book, and I felt so attached to the characters of Sunny and Snoozie that I wanted to continue on with them in another book and get to know them even better.

But I think what really interested me in this second book was the character of So-So. So-So’s backstory is that she lost someone very important to her, her friend Mickey, and she just couldn’t move on. She was so overcome by that loss because Mickey was everything to her: with Mickey, the world disappeared, and what was left was only Mickey—and then, Mickey was gone.

The story of Snoozie, Sunny, and So-So is about how friendship can help you move on from difficult situations. So-So meets Snoozie and Sunny, and something about their presence and this friendship in her life encourages her to move on. Yes, So-So lost something very important to her. But Snoozie and Sunny are there, too, and life keeps going on.

The most important thing the book explores is: how do you get over a loss? When I write, I’m basically always writing the same thing with different words, and loss and the way people can overcome all that we lose in life is one of the things that I find most interesting to write about.

At first, So-So is frightened of Sunny and Snoozie…

… but soon the trio are the best of friends!

ERW: That’s so important to explore, especially this year, when so much has been lost, with the pandemic and with everything else going on. The loss of lives, of health, of security, of routine, of expectations… But as you said, life keeps going on.

DBZ: This pandemic is still new, but maybe what we realize is that when you lose something, you gain something else. You have no choice but to gain something because everything you knew no longer exists, so you must find, or you must create, something else. That’s what creativity is to me: to create something out of what you have lost. And with the coronavirus, it’s the same kind of situation because everything we knew no longer exists, for now.

ERW: Exactly. So, first there was the picture book that was just about Snoozie and Sunny, and then came this second book that’s about Snoozie, Sunny, and So-So, which is maybe closer to a chapter book or lower middle grade book. How did you decide that this story with So-So was supposed to take this form, instead of a picture book like before?

DBZ: It’s not a decision that I made from the beginning. As I write, each book decides for itself. The first book had a very short text, and it was meant to be a picture book. But the second book had so many words that I had to make chapters so that it could be read more easily. And so, the book decides for itself.

The plot of the first book is very, very simple. Sunny, who is afraid of the rain, felt very bored because Snoozie was napping all the time, and so even though it was raining, Sunny decided to go out and ended up getting lost. (There it is again—as I told you, I’m interested in how you overcome loss and what can be created out of loss!) So, Sunny is lost, and then Snoozie, who never moves—in Hebrew, it sounds better because Snoozie’s name is “Zuzi”—

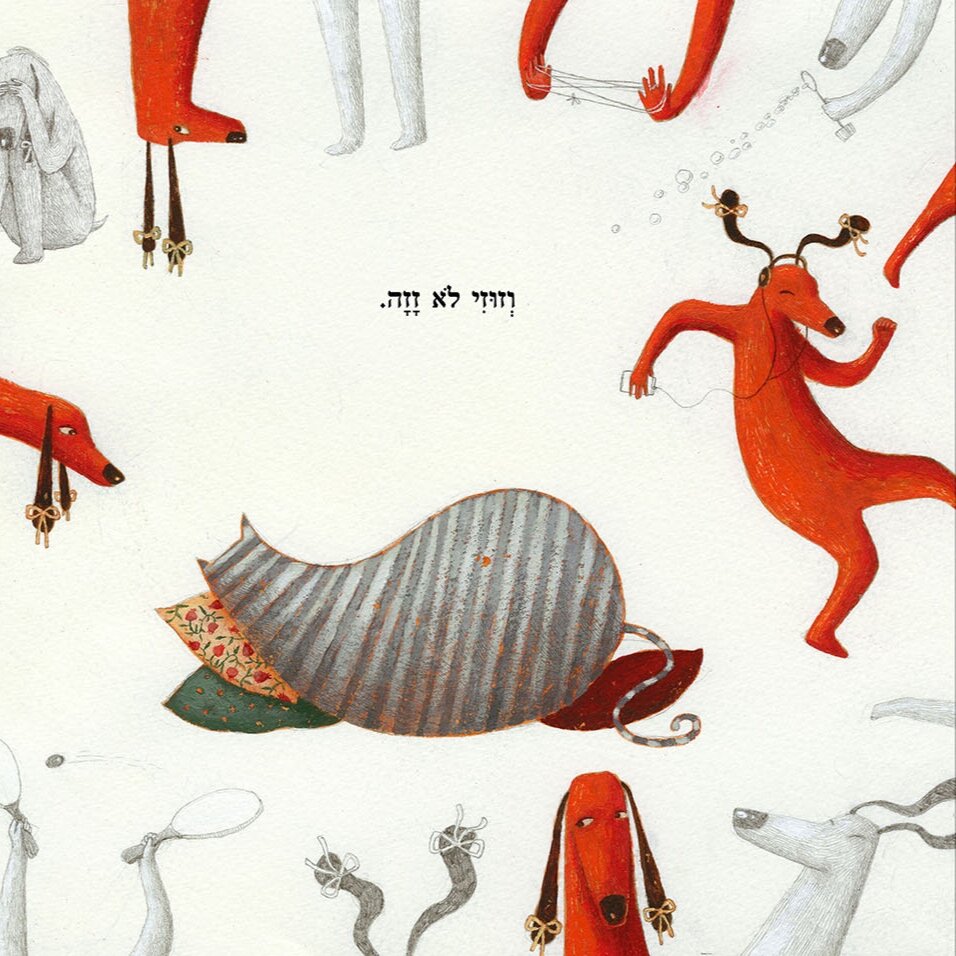

OA: “Zuzi” means something like “move on.”

DB: Yes, “move on!” In Hebrew, it’s “Zuzi lo zaza”: Snoozie never moves. But now, Snoozie has to move because Sunny is lost, so she goes out and looks for her. So, it was a very simple plot. But with Mickey and Snoozie and Sunny and So-So, it was a much more complicated story, with many more characters, so I had to divide it into chapters.

ERW: And here we are with a beautiful book! Ofra, did you feel like your approach changed from when you were illustrating a picture book to when it was more of a chapter book?

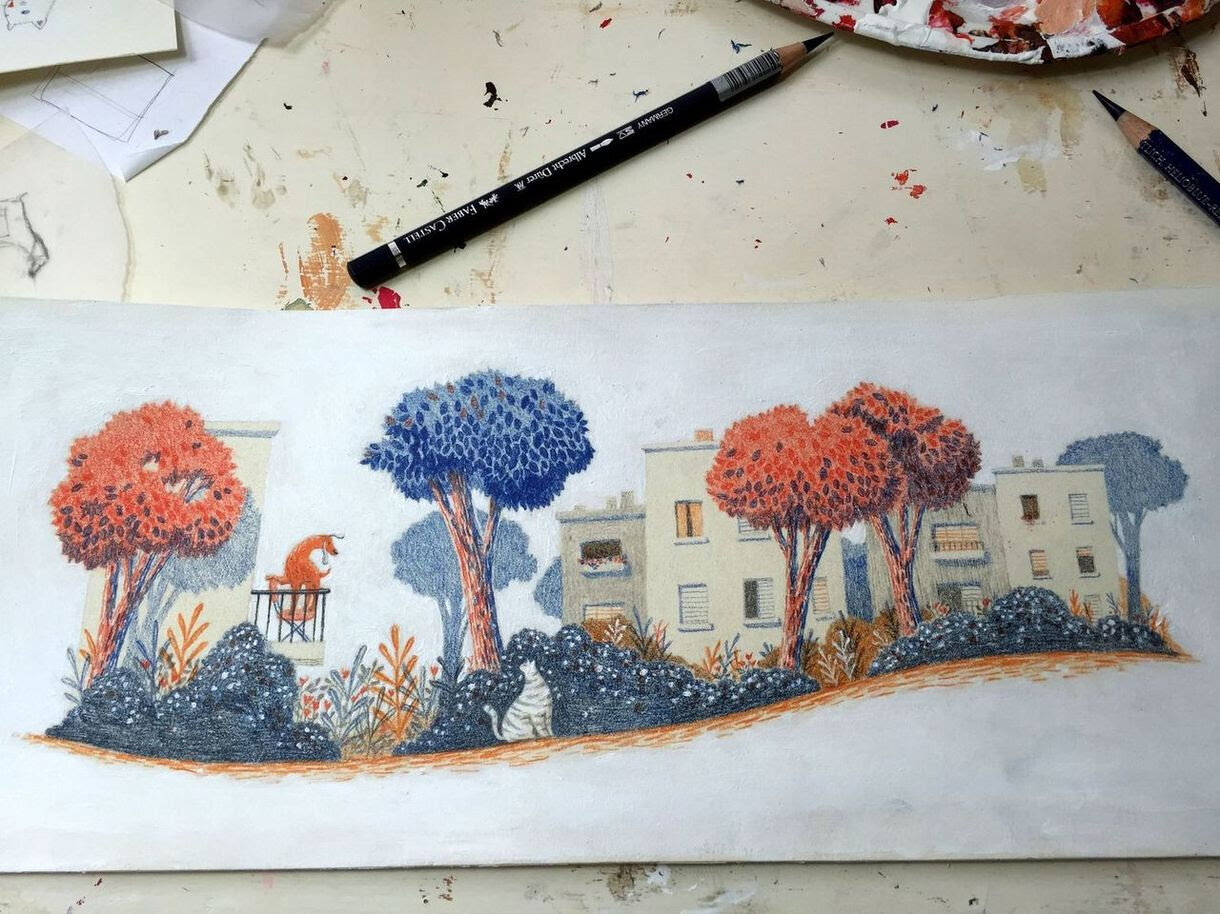

OA: My approach changed, but not because it was a picture book or not. It changed because there were a few years between the two books—maybe seven years, which is a long time. Naturally, I look at things differently and approach things differently after that much time, and I hope that in seven more years, I will look at things differently, too.

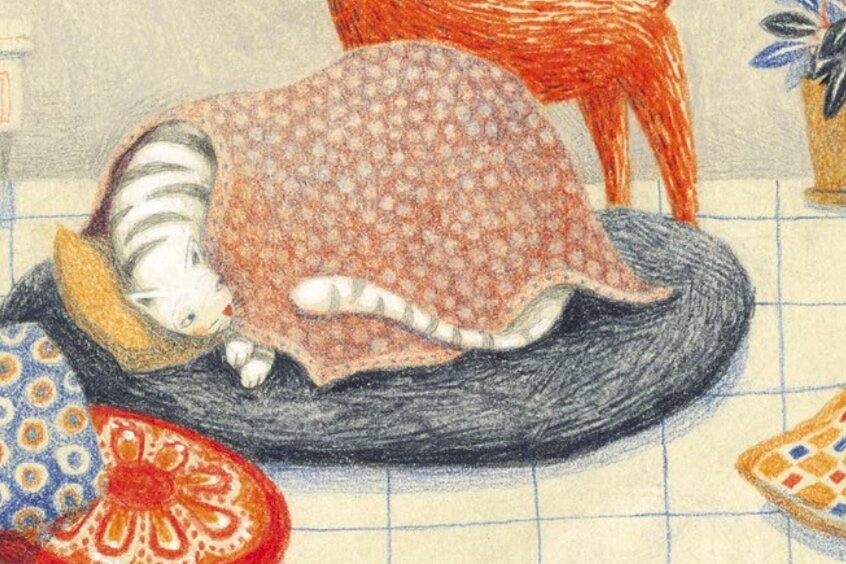

I like the change. I even changed the characters a little bit. It’s not the same art as in the picture book. It looks different, but it’s still similar enough so that you can recognize the characters, so kids in Israel can see them and know that it’s still Sunny and Snoozie. I also used different techniques: I used colored pencils in the second book, while the first book was in acrylic paint. It’s a big difference, but it’s not too far because of the audience age. Usually when I look back at old works of mine, I don’t like them as much as I did when I made them. I always want to make them different, so this was my chance to do it in a way that I thought would be better and more suitable.

In picture book Sunny and Snoozie, bold illustrations in acrylic paint

In chapter book Snoozie, Sunny, and So-So, soft illustrations in colored pencil in rich hues

ERW: Right, so you were coming back to this familiar story world, but with a different style because you had evolved as an artist. In a similar vein of melding old and new, how did you come up with how you were going to illustrate this new character of So-So?

OA: When I read the story and all the descriptions of So-So, it was so much like my dog that I knew exactly how to draw the character. I adopted my dog Toot when she was one year old, and I think she was suffering from some sort of previous violence or abuse. She came from the streets, and she’s very neurotic, but she’s found a good home. And she’s all these things that are described in the book: she’s shy, and she doesn’t have very many social skills, and I just couldn’t draw the character any other way. It’s really her—I mean, it’s almost realistic, and I couldn’t imagine it any other way.

ERW: Would you say that Snoozie and Sunny are also inspired by real animals, or are those characters more from your imagination?

OA: For Snoozie, Dafna actually had a cat, and her name was Zuzi.

DBZ: Yeah, she didn’t move a lot, and so we called her Zuzi. Almost all the characters in the children’s books that I write are based on real animals, on my pets. I really love animals, and they inspire me—not less, and maybe more than humans do!

OA: But what’s funny was that I never saw the real Snoozie: I never saw her, but after I made the character’s illustration, Dafna sent me a photo of the real cat, and she looks so similar!

ERW: It must have come through somehow through the writing! So then, how did this book come to be published by Enchanted Lion in English?

OA: Claudia got in touch with me. She wrote to me that she really liked the illustrations, and so she wanted to publish it. That’s how the English version came into the world.

DBZ: Didn’t it win first prize in—?

OA: It was in the competition of the Society of Illustrators. That’s how Claudia came across these illustrations, and she liked them, luckily, very luckily, and—

DBZ: And then she asked for the book—

OA: And the rest is history!

ERW: Well, we’re very, very happy that it ended up here with us and that we are able to share this story with English-language readers. And even though it’s in English instead of Hebrew, to me the text still feels very soft and gentle and poetic in a way, which can be really hard to translate. I feel like the translation kept not only the meaning, but also the way that the words feel and sound.

Encouraged by her new friends, So-So begins to write.

DBZ: Oh, I’m so happy to hear it! It’s hard to portray feelings. Often you can convey the meaning, but to express not only the meaning of the word, but also all its associations and feelings and rhythms…

OA: Dafna writes in Hebrew, and she often writes in verse, with rhymes. Since she writes poems, the sound of the words is very important in her writing, so it must have been quite a challenge to translate.

ERW: Dafna, as a poet, do you feel like your poetry has influenced your writing in prose?

DBZ: As a poet, I feel that when I write, the first thing that drives me and drives my words and moves the plot and motivates my work is the music of the words, and not their meaning. First of all, and above all else, comes the music. When my daughter was a baby, I sang lullabies to her, and it was a very good match: I could understand the meaning of the words, and she could enjoy the music. So, I’m always trying to reach that same kind of feeling of a good match with the music of the words.

It’s also like this with poetry: music is what moves me first of all, and only after comes the meaning. Poetry tries to bring back the music of the word. When we are little babies, the first thing we listen to is the music of the word. But then we lose this music, because it disappears when we start to attach to the meaning of the word. So, when I write, I’m always going back to the music of the words.

I’ve always thought that I was originally meant to be a musician. And now when I play, my instrument is words. Music is something to aspire to, something ideal to look up to, but my main instrument is words. And when you play with words, you can bring back the feelings, the sentiments, the emotions to the words. When we speak, I’m trying to say something, and we only hear the meaning and don’t hear the music. But when I write, it’s the music first of all.

ERW: Ofra, what about you? What would you say is the driving force in your art? What first draws you in to your illustrations, and what are you trying to go towards, or aim for in your art?

OA: Thinking of something that is parallel to what Dafna said about her writing, I am very much attracted to the feeling of the story. The emotions and the feelings are what I connect to when I draw. For example, when I’m illustrating a certain situation in a story, I wouldn’t immediately draw what’s actually happening in the scene. I’m more drawn to what the scene feels like and the atmosphere it creates from the point of view of the character, and what she feels, and what she thinks. Because reality is always subjective in the world of the drawing, and this subjectivity is very much what I am attached to.

Dafna said something about music as her ideal, as what she aspires to. I think that when I manage to find the visual language of the book, that’s when it truly becomes a lot of fun. At first, it’s very hard, and I’ll do anything other than sit down and work on developing the visual language.

The colors, on the other hand, are intuitive. I don’t think too much with colors, and that’s what I was reminded of when Dafna was talking about music as something very initial and intuitive. It’s something from your own very personal history, from your ancient history, from when you were just a little child. Some people find it easier to work intuitively all the time, but that’s not the case for me. But when I’m working with colors, it becomes this moment when I really feel just the same as I did as a child: if I feel like there must be a red spot there, then that’s the way it should be, and I don’t have or require any explanation for that.

Ofra’s early sketches of a scene after Snoozie and Sunny meet So-So for the first time

Ofra’s color tests to find the perfect shade of dazzling, vivid orange

ERW: I really love the color palette of the book, with the orange and blue and white and black. Just like in the story, there’s a lot of contrast between the different characters and the different colors, but somehow, they all seem to belong to the same universe and feeling, and they are very connected even in their differences. It’s really beautiful.

OA: Thank you. I’m really happy to hear that you feel this way. As an illustrator, you must really connect emotionally to the story, and sometimes you let things happen subconsciously, so it’s good to hear that you felt that emotion, too. It’s like I’m a director and you’re complimenting me on the visuals, so thank you.

ERW: Would you mind telling us a little bit more about how the two of you worked together on this book? Did you, Dafna, write the text in its entirety first, and then you, Ofra, illustrated it separately, or was it more of a back-and-forth collaboration?

OA: Well, because it was our third book together, we had a little bit of back-and-forth, but the story didn’t change much. We’re working on another book now, which is written but not completely finished, and I started illustrating it, and then it’s back to Dafna—

DBZ: And then I’m changing things, changing the characters and their personalities because of what Ofra shares—

OA: It’s like we’re one person! This new book is a picture book, and I share a lot of my work on this book with Dafna. Maybe not so much the pencil sketches, because I think that it looks so different when you illustrate things more completely, but yes: it’s very much a collaborative process.

Ofra’s studio

Dafna’s writing desk

ERW: How is it different to collaborate with somebody whom you know really well, with whom you have a relationship outside of work, versus somebody that the publishing house might just assign to you?

OA: Actually, in Israel, there is no such thing as working only in front of the editor; as an illustrator, you always work with the writer, with the editor also participating in discussions sometimes. But still, it’s not the same as when you get to know someone really well, and you are a close friend, and you know each other really well and you share so much with each other.

Dafna and I have a lot in common, in the way we look at books, and the way we look at childhood in general, and the way we look at sadness and loss, in many ways that are not often very welcome for some reason in children’s literature. So yes, it’s very different to work with a longstanding partner.

ERW: How would you describe that similar approach—to childhood, or books, or difficult times?

OA: I noticed that when I first started working as an illustrator, I used to make illustrations that looked sad or gloomy, and I got all these proposals to work on stories about the Holocaust. I did some wonderful projects, and then in the years that passed, I think I learned to better balance the good and the bad, the dark and the light. But my basic approach remained the same, because I think what I find most interesting is the imperfect, the imperfections of life…

When I illustrate children’s books, I don’t feel like I’m illustrating for children. It’s more like I am getting connected to the child that I once was. And there is a lot of pain and sadness in childhood, and I guess it comes out in a way. I don’t consciously set out to do illustrations for children, but I just approach it as if I’m a child, and so that’s the way my work comes out. It seems like that is my approach.

Dafna as a child

Ofra as a child

DBZ: I feel the same way. One thing that Ofra and I have in common is that we feel that children’s literature is not meant to deal only with happy endings. I think that it has to deal with sadness and also even depression. I don’t think I can think of a single issue that is not suitable for children (although maybe there are a few…). You can—and you must—say everything to children, but it all depends on how you are saying it.

For me, writing for children is everything! But it’s also much more challenging in a way, and much more complicated, because you have to say complicated things with simple words, so you have to find a simple way to express complicated ideas. The stories themselves don’t have to be simple—they have to say something real, and something about reality, and something about sadness, but just with simple words, which is always the challenge for me.

Like Ofra, for me childhood is also connected to pain and suffering. Because like many children’s authors, I had a really tough time in childhood. Maybe I’m writing for children as a kind of recovery, to build back up something that I lost, to come back to this Snoozie and Sunny kind of environment: to a moment when you know that everything will be good at the end, that even though there is much suffering and sadness and loneliness in my books, yes, in the end, everything is going to be okay. This is a kind of journey that you go through.

For more information and to purchase Snoozie, Sunny, and So-So, visit the book page here.

And you can read part two of the interview with illustrator Ofra Amit and author Dafna Ben-Zvi here!

Sunny and So-So, two friends playing together and enjoying each other’s company