A Toast to: Edward Lear & the Art of Nonsense — A Guest Blog Post from Warm as Toast

This is a guest post from Sophie Hoffer, which originally appeared on her Warm as Toast Substack. To read more of Sophie Hoffer’s pieces and to subscribe to Warm as Toast, which “celebrates children’s literature—no offspring required,” please click the button below.

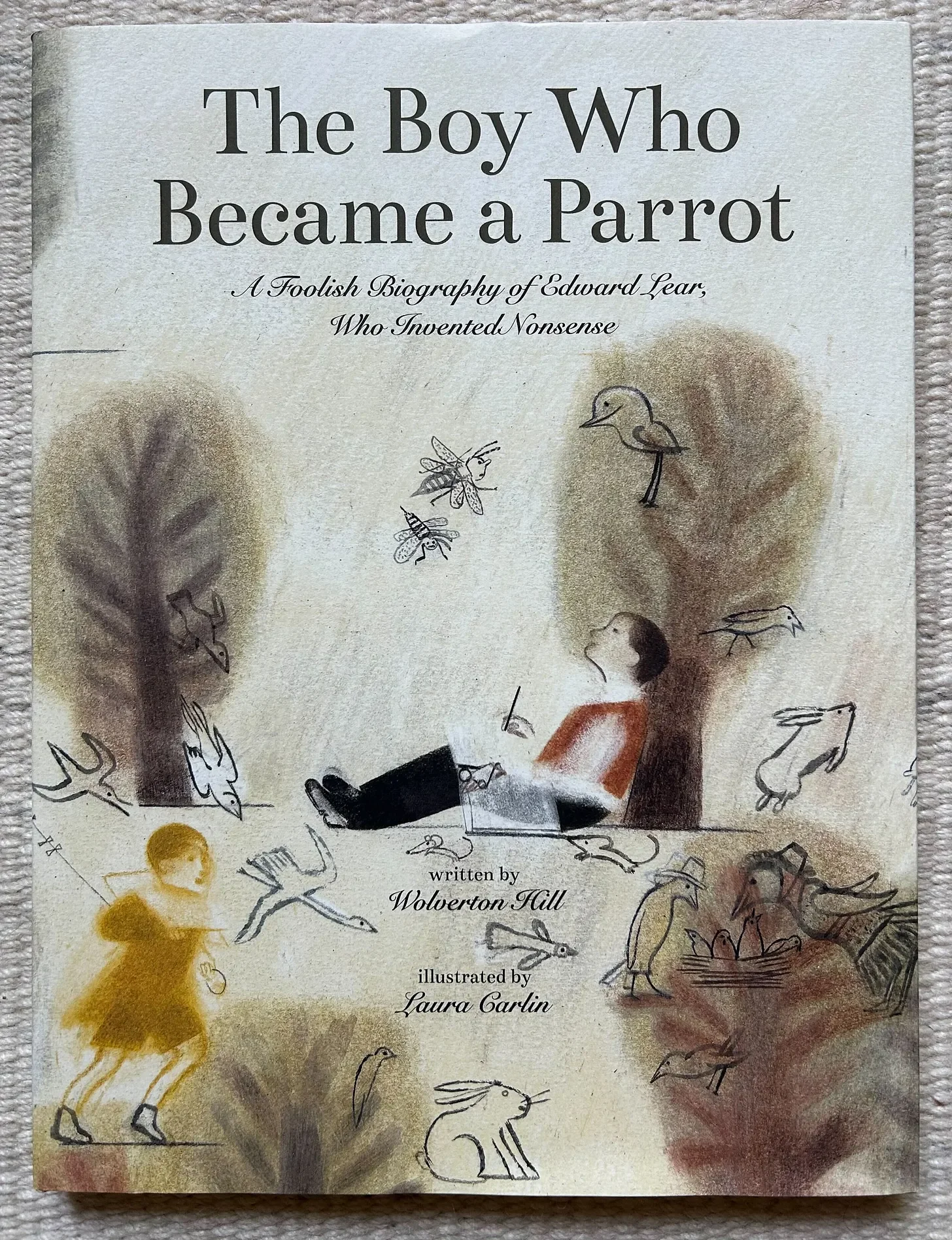

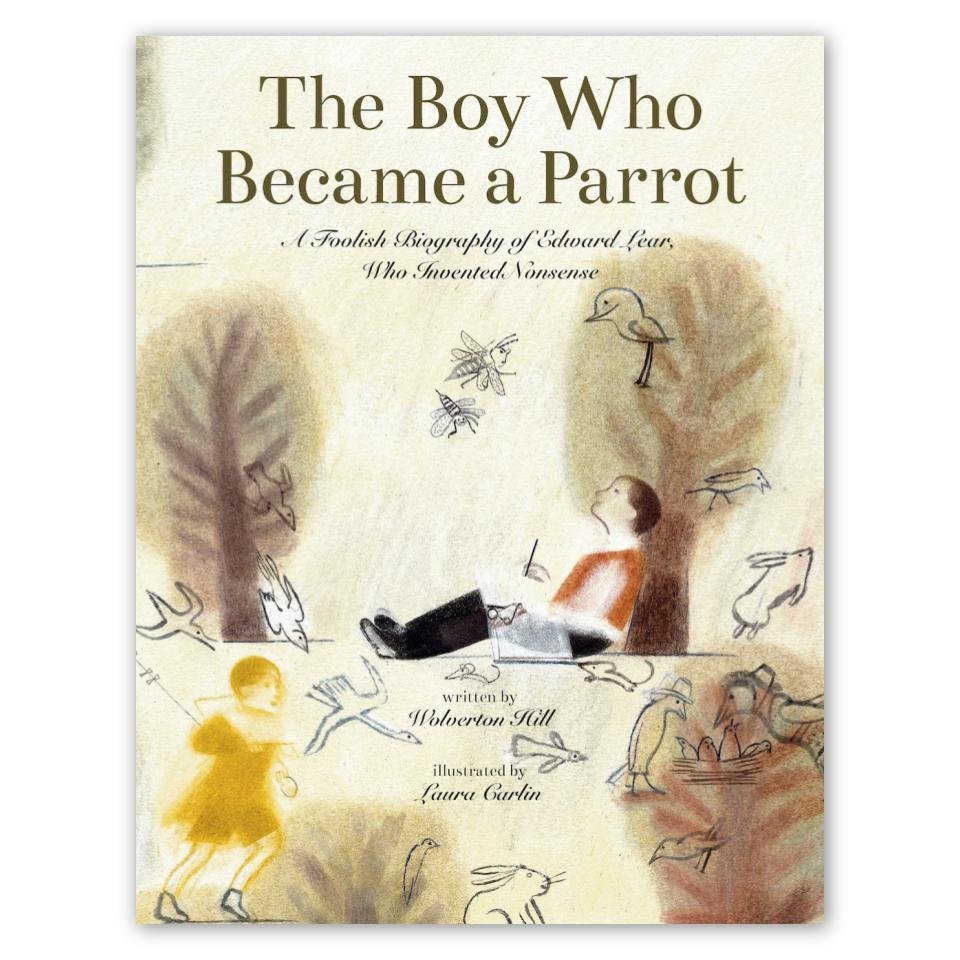

A preview of Enchanted Lion's forthcoming release, "The Boy Who Became a Parrot: A Foolish Biography of Edward Lear, Who Invented Nonsense" by Wolverton Hill and Laura Carlin

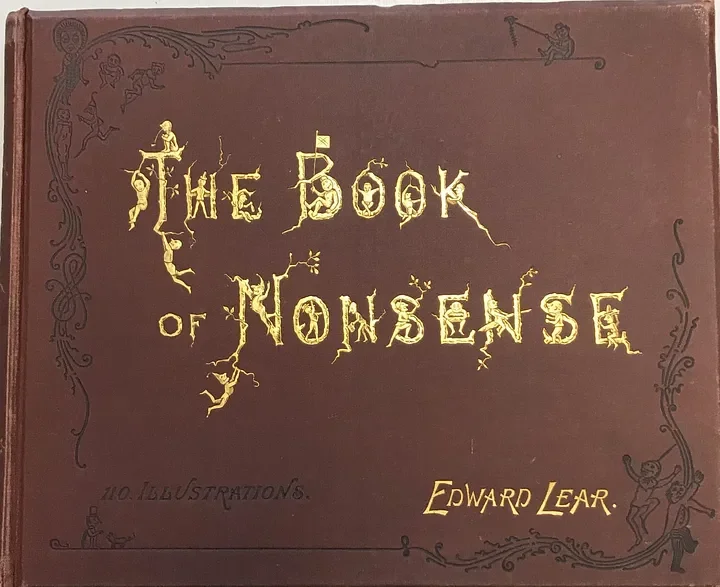

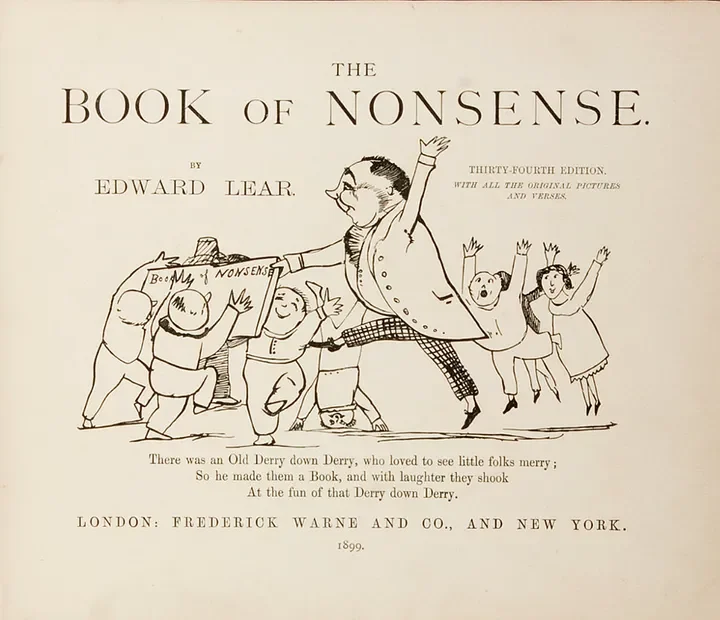

Edward Lear didn't just write nonsense, he transformed it into an art form. An illustrator by trade and poet by compulsion, Lear burst onto the children's literary scene in 1846 with The Book of Nonsense, a collection of limericks so bizarre, joyful, and defiantly unteachable that they redefined what a children's book could be. His world teemed with talking birds and plants that sprouted forks and spoons instead of flowers, where language itself took center stage and rules were gleefully abandoned.

"The Book of Nonsense" by Edward Lear (1846)

In an age of moral rectitude and instructional tales, Edward Lear's A Book of Nonsenseoffered neither lesson nor correction. As Sara Lodge writes in her insightful 2018 biography, Inventing Edward Lear, it "eschews didacticism" in a way that would have shocked its earliest readers. Victorian children's books were small, tidy, and preachy. Lear's was expansive, joyful, and wonderfully strange. With this book, Lear created space—literal space on the page—for children's minds to run wild.

Lear gave each limerick a full double-page spread, a layout that defied contemporary publishing norms. As both illustrator and designer, he gave his characters room to truly move. Bodies leap, tiptoe, and split in half. Limbs extend beyond margins. These weren't merely decorative illustrations but Lear's co-conspirators. "For Lear," Lodge observes, "word and image are not discrete entities… but organic branches with shared roots."

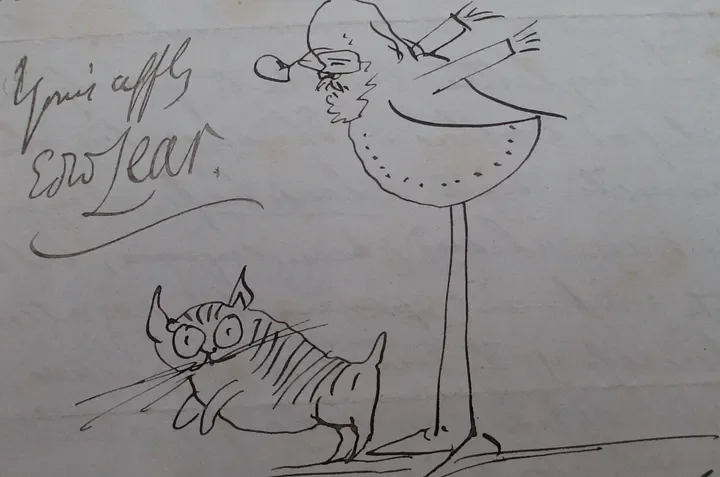

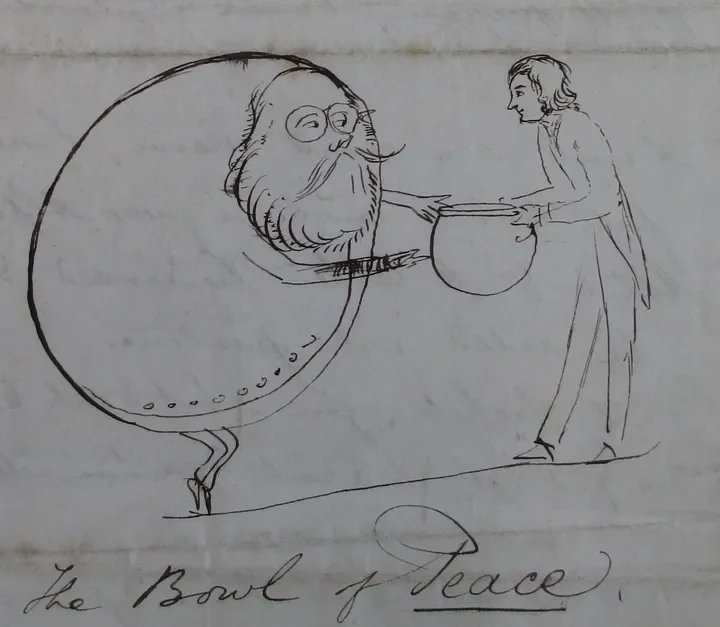

Yet something deeper lurks beneath the silliness. Lear's nonsense isn't simply childlike, it creates a bridge between childhood and adulthood. He famously sent "nonsense letters" to both children and adult friends, casting himself as a character who "chats with slugs, clings to wild sheep horns in Crete, or dangles in conversations with frogs." These letters, Lodge argues, "open up a channel of communication between the child-self and the adult-self." They seem to whisper: come back. Return to the version of yourself who once trusted the fantastical, whose imagination knew no bounds.

Images of Lear's letters sent to friends, housed at The Somerset Heritage Centre

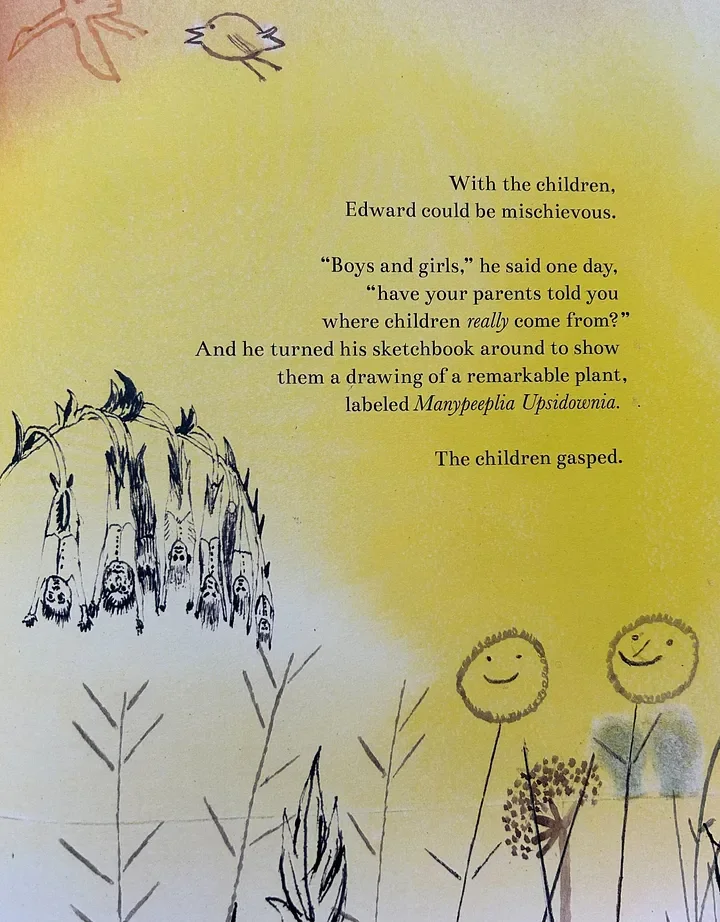

This vision of children as naturally imaginative, rebellious, and deserving of unfiltered joy distinguished Lear from the moral seriousness of his contemporaries. As Lodge writes, "Childhood is a state to be relished and cherished rather than reformed." Lear didn't try to correct children. He joined them.

Enchanted Lion's forthcoming release, The Boy Who Became a Parrot: A Foolish Biography of Edward Lear, Who Invented Nonsense, written by Wolverton Hill and illustrated by Laura Carlin, arrives July 29th and promises to share Lear's whimsy and wisdom with a new generation.

Biographies written for children often fall flat, reduced to sanitized timelines that drain the life from their subjects. I approached this one warily, fearing another dutiful march through dates and achievements (though, an Enchanted Lion title has yet to disappoint). Instead, I found myself immediately drawn in, my apprehension melting away in an instant.

Hill's deep knowledge of and love for Lear transforms what could have been a static portrait into something vibrant and alive. Rather than presenting a distant historical figure, Hill invites us to walk alongside a man whose struggles with depression, social anxiety, and the search for belonging feel startlingly contemporary. In a recent interview with Betsy Bird for the School Library Journal, Hill shared, "times have changed, but the fundamental challenges of growing up haven't. Lear met kids where they were, made them laugh, and showed them how the imagination can be an antidote against boredom, sadness, and injustice."

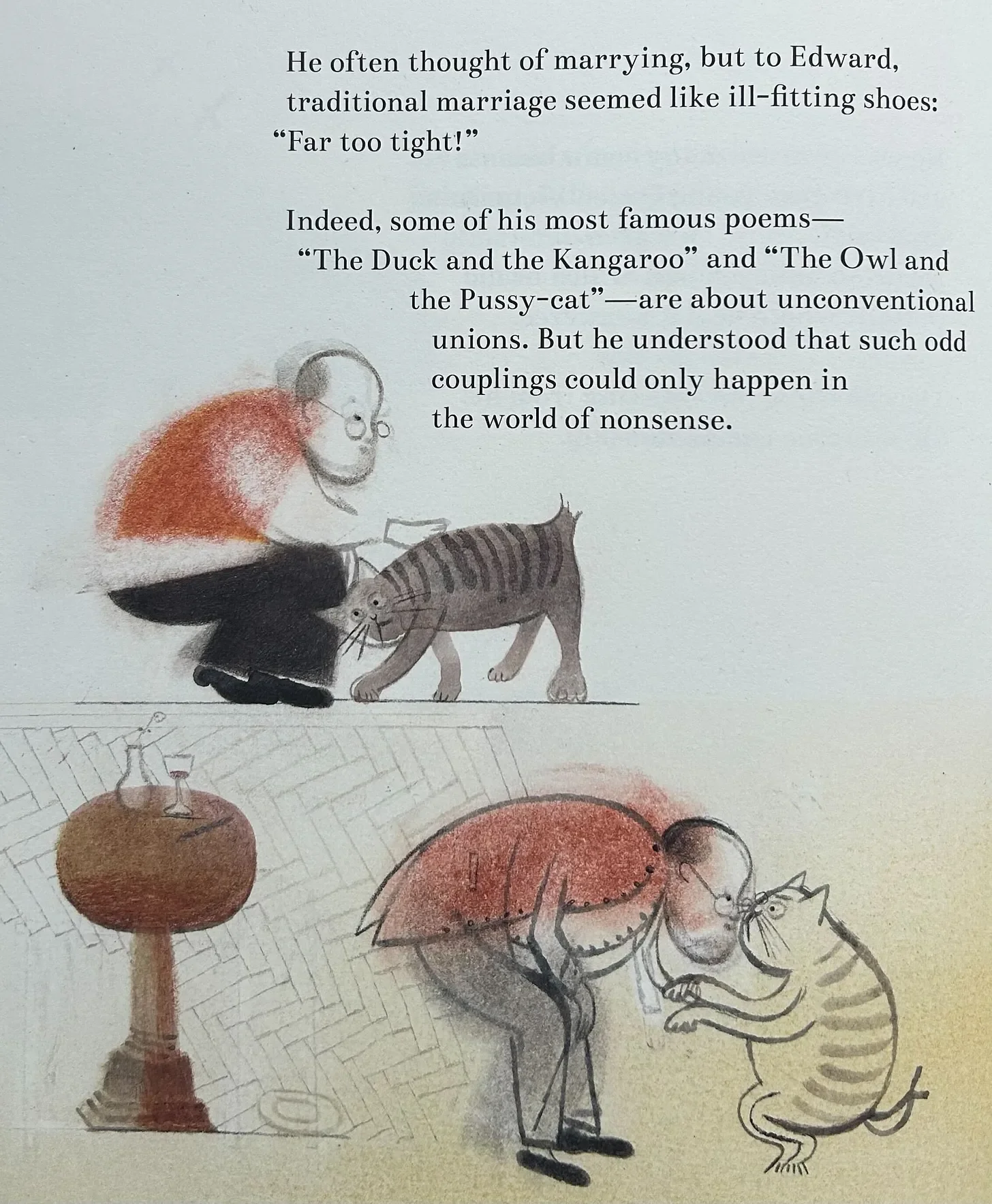

Crucially, this book refuses to sanitize the darker chapters of Lear's story. Financial hardship forced him from the family home as a child, leaving him to be raised by his sister. Epilepsy plagued him throughout his seventy-five years, a condition he called his "Demon." Despite public acclaim for his natural history illustrations, a persistent sense of not quite belonging shadowed him. As he aged, loneliness deepened, shaped by relationships and longings largely unspoken in the historical record. Hill handles these complexities with sensitivity, allowing readers of any age to grasp Lear's profound isolation without needing to explicitly state the truths his era demanded he conceal.

Hill's prose and Carlin's illustrations exist in seamless harmony. The artwork pulses with the same cadence as the narrative, forming a visual story that complements and elevates the written word. Carlin wields color like an emotional vocabulary—browns, blacks, and grays speak to melancholy and exclusion, while vibrant yellows, oranges, reds, and blues pulse with creative energy and connection. Most ingeniously, she weaves Lear's own artwork throughout, from his precise natural history drawings to the playful doodles that danced around his limericks.

Hill writes, “Nonsense offered a fabulous refuge from a real world that too often made no sense.” Today, when the horrors of reality feel unimaginable, this biography doubles as a survival guide. We need more than Lear’s permission to befriend slugs and chat with frogs. We need his defiance. Because in a world more absurd than any limerick, nonsense isn’t escapism. It’s perhaps the sanest response we have.

The Boy Who Became a Parrot: A Foolish Biography of Edward Lear, Who Invented Nonsense

Who was Edward Lear?

Edward Lear was a wildly imaginative man best known for his humorous short verse and "The Owl and the Pussy-cat" —Britain's most beloved children's poem. He was also a brilliant painter who saw beauty in people and places ignored by others. He loved animals, music, travel, chocolate shrimps, pancakes, and his cat, Foss. And unlike most grownups, he preferred children who sometimes misbehave.

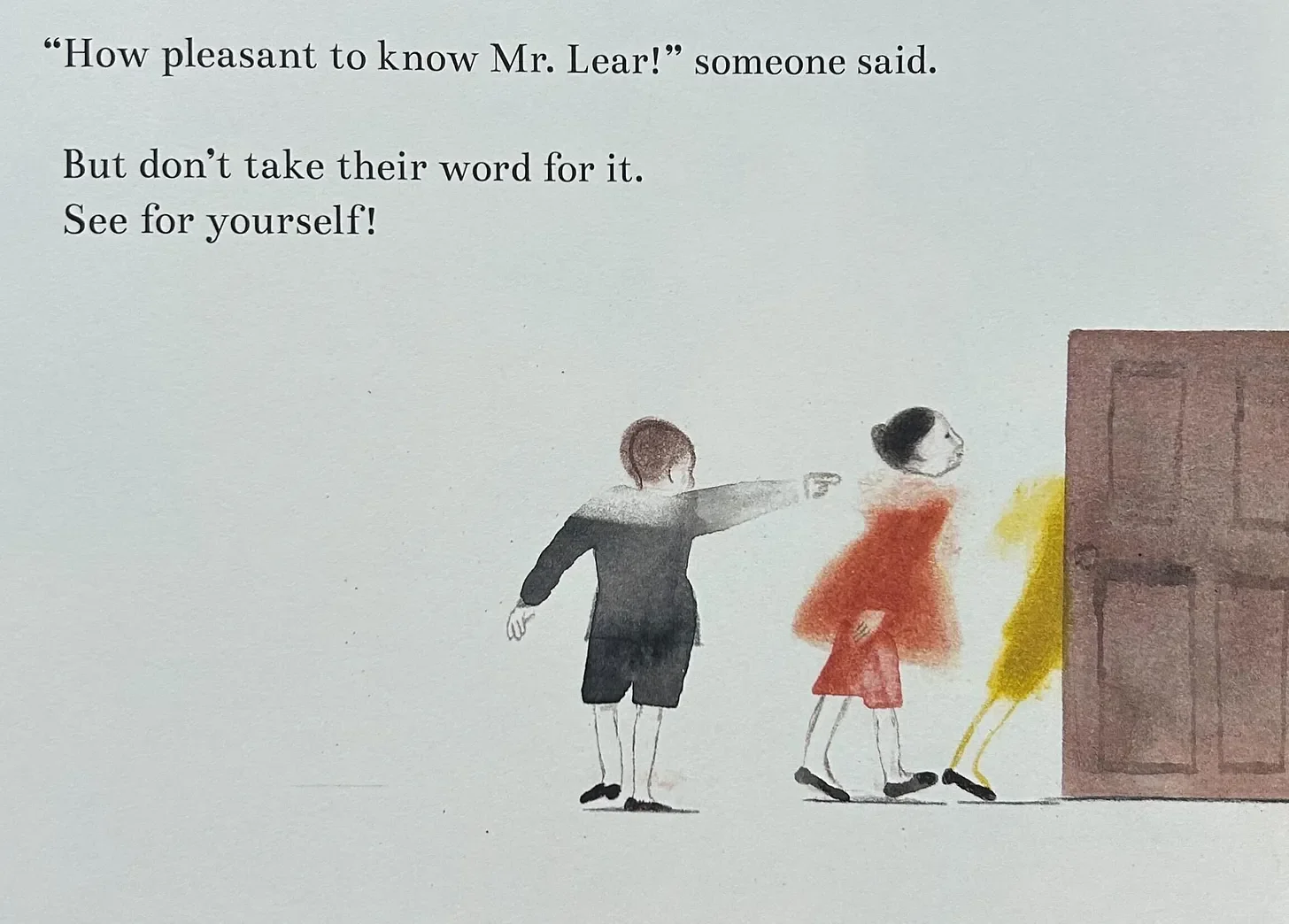

"How pleasant to know Mr. Lear!" someone said.

But don't take their word for it. See for yourself!

Click HERE to learn more & order the book!

Thanks for reading. If you enjoy children’s books and reading about them, and want to help keep Warm as Toast free for everyone, consider subscribing now for just $5/month. No offspring required.